On Equanimity

One of the biggest challenges you’ll faces as a technical co-founder of a social startup is that of equanimity.

You sit at the intersection of product and technology. The contrast in approaches in those areas is often under-stated and always under-recognized. In product, as CTO, you’re injected into the thought-stream torrent that results in strategic decision making, yet have little-to-no influence on the decision making process. Contrast with the technical world, where a startup CTO is given the keys to the car in regards to roadmap, technologies, and process.

It’s a dichotomy of roles for sure.

One might think that the divide between product strategy and tech is characterized by a language barrier between those that speak bits and bytes vs. those who don’t. But I think characterizing such as a digital divide doesn’t do us justice. Speaking code means that I am thinking about different things than those who don’t live and breath the technical minutiae of html tags, http sockets, 1s and 0s, hex color codes, if/else statements, do/while loops, free memory, and cpu utilization .

When the edge cases have edge cases

I am obsessed with edge cases. What happens if feature X is used in Y way? I’m constantly grasping with one of the core problems with running a social technology company. There is one variable that is greatly unknown to the technologist: the user. One’s mind is consumed with exploring the various possibilities as the blinking cursor haunts the empty source code file displayed in your IDE.

Technological direction is a core challenge. Wouldn’t it be cool if we built this feature with the latest & greatest? HTML5. Node.js. There’s a new ruby gem out that does that. Can’t CSS3 do that? Oh wait, we’re still supporting IE7. Whats our browser penetration there? Shit, we have a delivery deadline to meeting. Better get coding. Better to be wrong and ship than right and not shop, right?

The other half

How does the strategy team consume their time? Your guess may be just as good as mine, but I’d like to think I’ve spent enough time with them to make an educated guess. There are shades of grey, but I don’t think they don’t think about various edge cases as much as we do. They speak in MBA-nglish. Financials, legal, market share. On one hand their work is entirely emotionally expressive of the vision of the team. On the other extreme, supremely bland and detail oriented. They’re immersed in e-mail, photoshop, word documents, excel spreadsheets, and management software. Will the company have enough money to reach it’s next milestone? Do we have enough mindshare amongst investors? Amongst consumers? Engineering needs to ship that *yesterday* or we’re going to go bankrupt, oh and don’t forget the reporting piece, we’ve got data to collect.

Which all reminds me of a supremely articulate answer to the question: Do Artists and Technologists Create Things the Same Way? by Kellan Elliot-McCrea

I hesitate to generalize about all artists and all technologists. Which marks me right there, as an engineer by training. Trained to obsess about edge cases and tiny details — missing the forest for the trees makes no sense, the forest is just many individuals trees, repeated, at scale.

Which strikes to the heart of one of the key differences I’ve experienced watching and collaborating with artists.

As an engineer my creative act begins by removing ambiguity. What’s the simplest possible thing we can do? What’s the core of the idea? What’s the minimal viable product? When you say pigs should fly, is that sustained flight? Self powered? Do you mean flapping or simply moving through the air? Does flight imply control? Or would a porcine trebuchet get us to a version 1 beta? Maybe we could do some testing by putting a pig on top of a tall tower?

Artists I’ve worked with often take the opposite approach. How can we remove all the walls around this idea? How do we make the possibility space of this idea infinite? Flying pigs are really just an example of the impulse towards freedom that we’re trying to address, let’s not get too caught up on the pigs, or the flight.

Additionally as a technologist I’m often driven by an inner fantasy life of utility (and utopia) with a secret hope of broad impact. Artists seem compelled by the innate desire to express the inexpressible, and a secret hope of widely inspiring. Basely, the difference between being right and being true.

What’s striking about web startups is, that as a web startup, your product *is* your art.

Since we founded StepOut, I’ve noticed that everyone cares deeply about the output of their time. To some degree your identity is shaped by your hard work. This is the same for designers, engineers, and the biz dev team. If you’re an engineer of any level of passion, you care deeply about the product you are building, and such, emotionally connected to the design, the use, cases, the *flow* of the app. It’s *hard* not to be extremely opinionated about it’s direction and the priorities associated with the vision.

Often, I try to remind myself of faith in my team to make the right decisions. During that process, I’m remind myself of a personal trait that I’ve found encountered in a completely differently avenue of life, my daily meditation practice:

Equanimity (n) : mental or emotional stability or composure, especially under tension or strain; calmness; equilibrium.

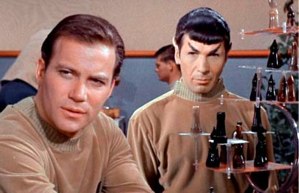

The key to equanimity as a startup CTO is to realize that you are building the knobs and levers that your co-founders are tweaking. You are building the starship enterprise as it is being flown, but you are *not* Captain Kirk. You’re Spock. You provide the data that decisions are based upon. Many times it’s delivered precisely. But sometimes the data is wrong. Sometimes a lever breaks. Other times, something gets lost in translation.

The curious thing about Spock is that as a Vulcan, he was *born* without emotions. As a technologist, you *learn* to be in control of yours, have faith in your team, and be equanimitous. It’s a skill that is not taught to engineers in trade school.

Be Spock, Not Kirk

It’s *hard* not to get emotionally attached to the results that the dozens of technical decisions you make daily deliver. At the end of the day. You’re tired. Remind yourself that this is when you have to be equanimitous.

Sometimes the data you’re presenting to your co-founders validates the vision you have for your business. Often times it doesn’t. When it doesn’t that’s when you have to be equanimitous.

We’ve made business strategy decisions based upon bad data before. Data that I provided. 4 months into execution of a business strategy that is unbearably flawed because of a bug you introduced, you need to hang your shame at the front door. Be equanimitous.

A member of your team is delivering good work. But they have personal traits that are abhorrable. Replacing them go would be hard. You must need to be equanimitous.

Feedback is delivered in less-than-constructive language. Take a deep breath and put the equanimity hat on.

Your job is to estimate specs so that your co-founders can decide what to build next. Resources are limited, but you strongly prefer one ticket over another. Equanimity up.

Long hours wear on you. Resources are thin. You’re at war, your team is your army, and you’re in a trench. Sometimes, it’s not easy to keep your cool. But it is essential . Or, as Spock would say, “You must learn to govern your passions or they will be your undoing.”.

Note: Any information of proprietary value to my employer has been removed or approved, and this post has been approved by my employer.