Situational Awareness

Software development is a somewhat abstract process and, often, estimating the path from feature ideation to completion is an exercise in guesswork. An unfortunate fact of life as a web engineer is that building blocks involved are often undocumented, unsupported, incomplete, and/or convoluted. If, like me, you work in a distributed environment, your different team members surely have different mental-models of the system. To create a realistic schedule, much less one that is cohesive enough to be relevant to your stakeholders’ needs, takes it’s fair share of understanding & communication.

Like many engineers, I’m fundamentally an introvert, and communication isn’t something that’s always come naturally to me. I’ve come to the conclusion that the best analogies for speaking about software development are the visual ones. Anyone can read a map — something about it is woven into our DNA. Perhaps it has something to do with humanity evolving a strong sense of visual back in our hunter gatherer days. In prehistoric times, on the plains of Africa, seeing a predator a 1/2 a second late was a matter of life and death. As such, natural selection has bequeathed to us, an sufficiently fast, effective visual processing system and memory.

Hacking a timeline

I read somewhere that the pneumonic devices that work best is to map ideas to physical areas of a room. If I must remember something in a particular order, I know I can focus on that object being located in a specific area of a location I am familiar with (my apartment, my walk to work, my office). The practice of recalling that information becomes as trivial as traversing that location in my mind.

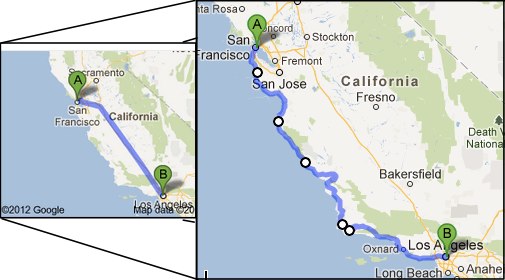

I’ve seen software roadmaps compared to maps of physical loctions. In a fantastic Quora essay by Michael Wolfe, he compares the development of a major feature to a hike down the California coast. In his example, one can estimate a timeline and pace for the entirety of the trip. But only once one carefully considers the trip’s terrain, equipment, the weather forecast, the experience and gumption of the team members involved, can one really create a reliable estimate. And even then, the estimate is subject to the a million little twists & turns as the journey progresses.

I’ve seen software roadmaps compared to maps of physical loctions. In a fantastic Quora essay by Michael Wolfe, he compares the development of a major feature to a hike down the California coast. In his example, one can estimate a timeline and pace for the entirety of the trip. But only once one carefully considers the trip’s terrain, equipment, the weather forecast, the experience and gumption of the team members involved, can one really create a reliable estimate. And even then, the estimate is subject to the a million little twists & turns as the journey progresses.

Investing in things you can control

One thing I’ve been coaching, in myself and others, for the last year is something called situational awareness. It’s not something they teach in grade-school, so let’s go to Wikiepdia for a definition:

Situational awareness is the perception of environmental elements with respect to time and/or space, the comprehension of their meaning, and the projection of their status after some variable has changed, such as time.

In other words, wherever you are in your journey, development or otherwise, make sure you have situational awareness of the conditions around you and situational understanding of the goals of your task. Always being re-evaluating the ‘terrain’, and check the pulse of the ‘weather’. And you must be honest about the conditions around you. Then can you grasp where you are and where you need to go.

Mind & Muscle

I’ve been running for almost a decade now, and like friend & mentor Brad Feld, I have a huge thighs. In fact, prior to writing this post, I was on a 10-mile trailrun. Because I’ve invested so much in my legs, I can do a several mile run at the drop of a hat. As I’ve trained better, harder, & more often, something unexpected has happened: I’ve now got the intuition to know how far and how fast I can go because I’m always aware of my stamina, gumption, pace, and heart-rate.

Likewise, the more I’ve built web apps, I’ve gotten good at using an IDE. I’ve also got a firm grip on how far and how fast the team can go because I’ve developed intuition for who’s good at what, where bugs may be introduced, where maintainability/performance anti-patterns or communication gaps exist, and what it takes to tackle those pitfalls.

The more you invest in the things you can control, the better you get at what you’re doing. The practice of honing your skills supports your awareness, and visa versa. The feedback loop is what’s important. Situational awareness comes from practice, reading the data, thoughtful developing pattern recognition.

In Practice

Once you’ve got the metrics-gathering part down (for running & hiking, I’ve got a garmin watch) , you learn to make decisions based on data. I’ve found the following to be effective ways to facilitate my software situational awareness:

- Automate reports which serve as status indicators — invest in some good automated testing, logging, & reporting.

- A daily, weekly, and monthly data-gathering routine.

- Recognize that mental downtime is a good thing. Disconnect from the grid daily, and at least one weekend a month. Go on runs or go hiking.

- Find and engage great mentors — especially with great entrepeneurs!.

Has something worked well for you? Leave a comment below.